Setting up the seance

Making it happen

Sometimes I think Kreskin is trying to hypnotize me. His drawling emphasis and repetition of instructions make me wonder if he can read your mind or merely make your mind think what he wants it to, so as to seem as if he knows what you are thinking. Either way, he's in there.

When the record was over, I wanted to hear Mick Jagger's 'Invocation of my Demon Brother'

Mick on Moog for the 1968 Kenneth Anger movie

Listening to the eleven-minute song, I started looking through old print copies of The Economist magazine online. An article from the first print edition, September 2nd, 1843, caught my eye.

"Dreadful Murder," Economist Magazine, September 2, 1843

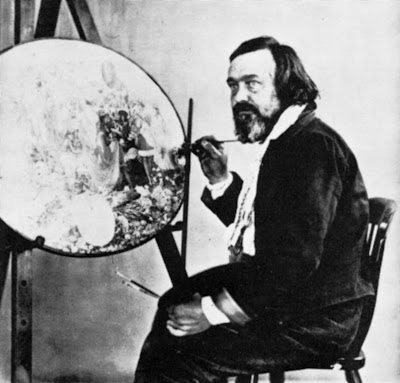

The man murdered is a chemist named Robert Dadd. His son, "Richard Dadd, a fine young man, 24 years age, committed the act whilst labouring under an aberration of intellect." Richard Dadd was a painter, best known for the maddened detail of the paintings composed while at Bedlam for the murder of his father.

'The Fairy-Feller's Master stroke' took him nine years to complete. He worked with the single hair of a brush, reciting poetry and staring at the canvas until the next element was revealed to him.

It was initially believed that he was suffering from sunstroke caused by an extended trip in 1842 through Athens, via Corfu, then Smyrna, Constantinople, Asia Minor, Rhodes, Cyprus, Beirut, Tripoli, then walking and by mule, into Damascus and finally Jerusalem. From the Dead Sea, he took a boat up the Nile to Thebes, arriving around Christmas. In retrospect, Dadd's affliction seems more like Jerusalem Syndrome--the vision of Osiris in ancient lands.

Dadd's journal in Egypt reads:

Did he turn to look at me, from his lion bed of birth and death? I believe that I saw it, the tilt of his carved face, the shifting of the soot that hid him. Did Isis and Nephthys pause in their frozen motions of revival to flick an inscrutable gesture at me with their fingers? I do not know what I saw, I do not trust my eyes, but I am sure that I heard him. In the temple of Opet he spoke to me; he spoke truths too great to hold. That is why I do not remember his words. The ecstasy of his voice and meaning overwhelmed me but the words do not matter. I am his chosen and he suffuses me.

Days have passed; days in which I doubted the truth that Osiris has given to me, and thought myself possessed of evil. But the truth of my fate is with me and I cannot doubt it.

Phillips is here with me now. His eyes are tiny and distant and I wonder if he too suspects the things that will be coming after us, but I think not. The air is greasy with the burnt caramel fetor of his pipe. I share his smoke and the world slows. For a moment I am calm and I grin foolishly at Phillips. That is when the burning begins, but it is only in my eyes and I think that it is just the smoke. I rub at them and my fingers begin to sting. Phillips says something, he is asking if I am all right, his eyes focus on me through the haze of smoke and I try to say that I am fine. The words leave me, I feel them go, my mouth forms into communicative shapes and they are gone to swirl with the smoke, forming new patterns as they mingle and breed. I cannot hear them. I say 'I cannot hear the words' but those words flutter up with the others. Phillips is speaking again but his words do not hold any meaning, he has invented a new language, it is a trick. His words have sound but no meaning. We must be opposites, he and I. It is a sign that he is my opposite. His moustache bristles; isn't that the word? That's what moustaches do, they bristle. Each hair is perfectly clear : I could count them if I wanted, but my eyes will not stay still and they burn. The sweet taint of the opium is sitting on my mind, binding my thoughts like tar. He is moving : Phillips is looming, getting closer. He touches my shoulder and says something in his new not-language and that is when the crush of thoughts and the blanket of opium-calm over them ignite into pain, and I remember nothing more but the screams that tear at my throat.

Osiris had entered his soul. He would never release himself from that influence. Having killed his father, Dadd fled to Paris, attempted another murder along the way and was captured outside Calais. Before he had killed his father, he had 'killed' many others, including his traveling partner, Philips:

This morning I killed Phillips. I waited for him in his room. I had his razor. His own razor, still a little sticky with his shaving soap. I stared at the patterns on it as I waited for him. I could see them in the corners of the room. They are always there now, at the corners of my vision, darting before me, dancing, fornicating, twisting over the ceiling, their tiny faces contorted and gleeful, their voices high and constant and through their chatter I hear His voice, deeper and compelling, telling me over and over that Phillips is not to be trusted, that he is evil and that he will deceive me if I let him. I kept my eyes on the smudges of soap because I did not want to see them, did not need to see them. It was not decent that they could be so pleased at what I was there to do. Not decent that I shared their elation when I must be composed. I must be calm to carry out the act.

I was sure, then. I brimmed with certainty, the doubts belonged to someone else, a me who was not me. I turned them over, the thoughts of the not me. The thoughts that tell me that the voices are not true, that Phillips is my friend, that I am scaring him. I smiled as I dismissed those thoughts and exhilaration tingled in my skin.

Phillips came in and frowned to see me in his room. I told him that I knew of his evil and my voice rang with Their power. I told him that I would bring justice upon him. I hit him to the floor and pinned him there. My hand was over his mouth, forcing his head back. His eyes were dreadfully wide; his breath on my hand was hot and quick. I noticed that his collar had been done up too tight and had made his neck red. He hardly struggled at all. He did not have time. I ran the blade over his throat with a firm quick movement and the blood that poured out bubbled a little.

As I watched the focus of his eyes slip away from me, dip into nothingness, he walked in the door. There was nothing in my hands. The razor was gone.

'I killed you. I killed you just now. Must I kill you again?' I heard myself speak and it was my own voice, weak and faltering. The power was gone. I had failed and they had repudiated me for it. I leapt at Phillips, sure that if I killed him again they would come back to me and I would be certain again. I wanted to cut his throat and see him bleed again but the blade was gone, so I clawed at him and tried to throttle him. There was no strength in my hands. My limbs quivered and I fell to the floor when he pushed me and did not get up. I sat and wept like a scorned woman.

For an age Phillips stood where I had attacked him and stared at me as though he did not know me. I crawled away from him and hid my face in the valance at the foot of the bed. When he spoke his voice was unsteady.

'Richard, you must get help. This is not sunstroke.'

I could not answer him and he did not say anything more. When he left he locked the door.

Dadd was convinced that he was being beckoned by Osiris to wage war against the demons. Dadd's journal:

There are angels and demons in the world. Spirits of power and beauty, and of curdling horror. And there are the lesser spirits, the fairies, who are to us as deer are to horses but who share our mixture of the divine and the wretched. They speak to me and tug coyly at my spirit and they are wondrous to behold.

I tried to escape them, when I came back. I threw myself into my old life, as though I could fit myself back into the narrow rut that I had sprung from. I tried not to see. The competition was a mistake, a distraction, trying to escape their influence through feverish days and nights of work, design after design. But it was for nothing. The spirits would not let me be, and they saw to it that I failed.

There are things that go unseen, things that walk in the skins of men, but evil has crept into their flesh and hollowed them out. They are hollow men who smile and talk and act as men do to hide the malignant swirled emptiness inside. But I walk with angels and demons and it is my curse that I can see those who are marked with emptiness. I walk with angels and demons and I see…

Disentanglings: Dadd would die in Bedlam, having been committed there for the murder of his father when he was 24 years old. It is exactly 165 years to the day, today, October 31, 2008, that Dadd was captured outside Calais. The more I have researched him, the greater the assonance:

There was a painting that caught my eye at the center for British Art on the first day that I moved to Yale. I stared at it for what could have been a few, drawn-out minutes, or a rapid half-hour or an hour. I know now that it was a Richard Dadd.

Invocation

"Osiris is quite different, he demands sympathy. He is the completely helpless one, the essential victim. Yet he is avenged and his passion has an end at last, when justice and order are re-established on earth. The other gods are transcendent, distinct from their worshipers. Osiris, however, is immanent. He is the sufferer with all mortality but at the same time he is the power of revival and fertility in the world. He is the power of growth in plants and of reproduction in animals and human beings. He is both dead and the source of all living. Hence to become Osiris is to become one with the cosmic cycles of death and rebirth." (R.T. Rundle Clark, 1859)

The Master at Bedlam, Dr. William Hood, wrote about Dadd:

Dadd paints in a bare room in daylight. He uses two easels, one bearing the painting and the other a palette. He holds a brush in his right hand and a magnifying-glass in his left, and often the brush has but a single hair. The fineness of the detail he paints is extreme, and sometimes quite imperceptible, to me at any rate. Sometimes he will remain motionless for minutes on end, with the brush-tip against the canvas and the glass in close proximity. As he works, he often chants his verse, or makes hissing sounds in the manner of an animal.

Haydon, for his part, is greatly changed in his opinion of both the painting and its executor. From a former estimation of gratitude and pride, he has progressed through fascination and revulsion to an attitude today that is not so very far removed from terror. Dadd has asked the steward to pose for him, and so to be put into the picture, but Haydon will have no such thing. Asked why he then continues to wear Dadd’s ring, the unhappy steward has been heard to claim that its jewel serves as a charm against evil.

'He lives there and there he is. At Harvest's end his year begins'