In a conflation of film and material composition, Stanley Kubrick’s Barry Lyndon could be described as an aesthetic experiment of painting time. In similar spirit to Horace’s ut pictora, poesis, the film hovers around a theoretical platform that could be articulated as something like ut pictora, cinematographeum. Kubrick frames sequences in such a way that the imminence of an event is repeatedly dramatized—flattening out the action by emphasizing imminence over outcome. Everything has already happened in the film and we are watching depictions. The narrator tells the viewer that something is about to happen and, as the action moves unhurriedly toward that event, the imminence of the event suffuses, slows and beautifies the scene. It is, in sum, an aesthetic mode characterized by portraiture. This is accomplished by a narrator repeatedly suggesting what is about to happen (affording the viewer a sense of totality—in that the narrator already knows the entire story), by the sluggish movement toward the upshot of sequences (focusing attention on the imminence of the impending outcome of a sequence), and by the sheer, oiled, elegantly still look of the film. The viewer is, in a sense, constantly waiting for the film to come to life.

Throughout Barry Lyndon, the narrator alludes to the notion that he knows what is going to happen because it has already happened. He dramatizes impending action to the viewer with phrases such as, “fate did not intend that he should remain long in the service and an accident occurred which took him out of the service in a rather singular manner,” just before Barry steals Lt. Jonathan Fakenham’s outfit and enters Prussia. Elsewhere: “He had for some time now ingratiated himself considerably with Captain Potzdorf, whose confidence in him was about to bring its reward,” just before he is put into the service of the Chevalier de Balibari. And: “There is many a man who would not understand the cause of the burst of feeling that was now about to take place,” just before Barry reveals his identity to the Chevalier, initiating the relationship that would shape his career as a professional gambler. The action is not happening as we watch the film. It has already happened and is rather being depicted for the viewer. The narrator knows the entire story. The implication for the film’s sense of time is that it is a closed phenomenon. Such totality suggests that the entire story is already spread out and complete, like a finished painting happening in front of our eyes.

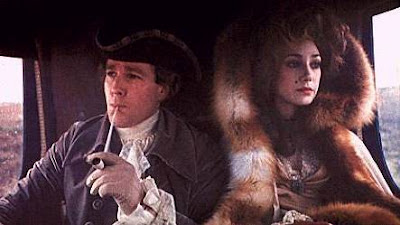

Having constructed a narrative frame that focuses attention on the finished totality of the film’s sequences and on the film as a whole, Kubrick highlights this flatness in time by showing actions moving unhurriedly toward an outcome. The lengthy duel scenes are less concerned with the outcome of the pistol shots than with the procedural tedium and elegant posture of the events. We see this in the gambling scenes as well. The action moves unhurriedly from one bet to the next, focusing instead on Barry’s staring at Lady Lyndon and on her staring back at Barry and on Barry catching her gaze and the two staring at each other. When Barry steps outside to meet Lady Lyndon on the balcony, neither says anything to the other. At a certain (meta-) register, it is unnecessary: They are already together and we are instead more intently watching the grace of their courtship, the steadily unfolding strokes of their romance. The robust textures of the film’s sequences surface from delay and detail to manner. The imminence of outcomes is nearly palpable and trumps the importance of narrative timeliness. We are encouraged to watch slowly—to experience the film as we might a painting.

Another quality of the film that immediately evokes portraiture is the sheer painted look of many scenes. After Lady Lyndon catches Barry in the garden with one of her maids, she is shown in her tub, half-naked and in a kind of stupor. Her body and face shine softly with an oiled stillness. The camera pulls away and she does not move. We are literally looking at an embodiment of flat elegance, of painting. She is elsewhere described by the narrator as occupying a place “not very much more important than the elegant carpets and pictures which would form the pleasant background of [Barry’s] existence.” And, beyond the almost explicit portraiture of Lady Lyndon, the film constantly hangs on painterly expanses, from the idyllic field where Barry’s father is killed to the lush lakes around the Countess of Lyndon’s castle. In many of these scenes there is a lack of visible differentiation in detail between the foreground and the back—a lack of depth—which is literally a flattening of the visual field.

Outside of the painted look of the film and its framing of narrative action around the imminence of events (thus flattening time), flatness in Barry Lyndon inhabits a greater, ontological argument. The epilogue reads:

IT WAS IN THE REIGN OF GEORGE III THAT THE AFORESAD PERSONAGES LIVED AND QUARELLED; GOOD OR BAD, HANDSOME OR UGLY, RICH OR POOR THEY ARE ALL EQUAL NOW

In the same scope that the narrator is ubiquitous across the time, the persons narrated in the story are equal upon the final account of the film. They are flattened in the hands of history. Much like the scenes of the 18c European paintings that are the film’s aesthetic reference point, the film’s sense of history is of a totality upon canvas. All players are together now and, taking account of the film’s narrative frame as premise for understanding history on an axis of ubiquitous presence, all players are carrying out their action in perpetuity. Or, rather, given the film’s insistence upon the import of imminence over upshot, all players are perpetually about to be embroiled in action. Beauty and grace in each player’s portrait surface instead from attention to detail and manner before impending, inevitable ends.

No comments:

Post a Comment